reading-notes

https://faroukibrahim-fii.github.io/reading-notes/

Pythonisms

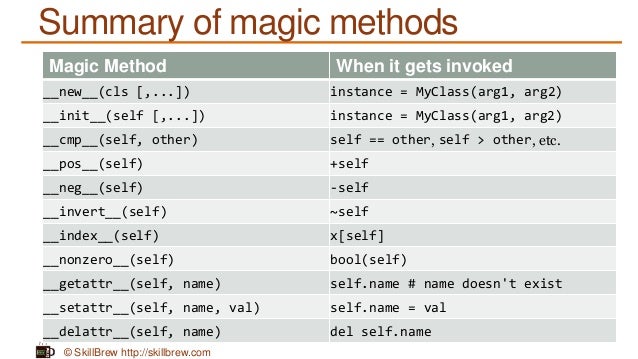

Dunder (Magic, Special) Methods

What Are Dunder Methods?

In Python, special methods are a set of predefined methods you can use to enrich your classes. They are easy to recognize because they start and end with double underscores, for example init or str.

As it quickly became tiresome to say under-under-method-under-under Pythonistas adopted the term “dunder methods”, a short form of “double under.”

These “dunders” or “special methods” in Python are also sometimes called “magic methods.” But using this terminology can make them seem more complicated than they really are—at the end of the day there’s nothing “magical” about them. You should treat these methods like a normal language feature.

class NoLenSupport:

pass

>>> obj = NoLenSupport()

>>> len(obj)

TypeError: "object of type 'NoLenSupport' has no len()"

To fix this, you can add a len dunder method to your class:

class LenSupport:

def __len__(self):

return 42

>>> obj = LenSupport()

>>> len(obj)

42

Object Initialization: init

Right upon starting my class I already need a special method. To construct account objects from the Account class I need a constructor which in Python is the init dunder:

class Account:

"""A simple account class"""

def __init__(self, owner, amount=0):

"""

This is the constructor that lets us create

objects from this class

"""

self.owner = owner

self.amount = amount

self._transactions = []

Object Representation: str, repr

It’s common practice in Python to provide a string representation of your object for the consumer of your class (a bit like API documentation.) There are two ways to do this using dunder methods:

-

repr: The “official” string representation of an object. This is how you would make an object of the class. The goal of repr is to be unambiguous.

-

str: The “informal” or nicely printable string representation of an object. This is for the enduser.

Iteration: len, getitem, reversed

In order to iterate over our account object I need to add some transactions. So first, I’ll define a simple method to add transactions. I’ll keep it simple because this is just setup code to explain dunder methods, and not a production-ready accounting system:

def add_transaction(self, amount):

if not isinstance(amount, int):

raise ValueError('please use int for amount')

self._transactions.append(amount)

Operator Overloading for Comparing Accounts: eq, lt

We all write dozens of statements daily to compare Python objects:

>>> 2 > 1

True

>>> 'a' > 'b'

False

This feels completely natural, but it’s actually quite amazing what happens behind the scenes here. Why does > work equally well on integers, strings and other objects (as long as they are the same type)? This polymorphic behavior is possible because these objects implement one or more comparison dunder methods.

An easy way to verify this is to use the dir() builtin:

>>> dir('a')

['__add__',

...

'__eq__', <---------------

'__format__',

'__ge__', <---------------

'__getattribute__',

'__getitem__',

'__getnewargs__',

'__gt__', <---------------

...]

Python Iterators

Python Iterators That Iterate Forever

We’ll begin by writing a class that demonstrates the bare-bones iterator protocol in Python. The example I’m using here might look different from the examples you’ve seen in other iterator tutorials, but bear with me. I think doing it this way gives you a more applicable understanding of how iterators work in Python.

Over the next few paragraphs we’re going to implement a class called Repeater that can be iterated over with a for-in loop, like so:

repeater = Repeater('Hello')

for item in repeater:

print(item)

In this code example, Repeater and RepeaterIterator are working together to support Python’s iterator protocol. The two dunder methods we defined, iter and next, are the key to making a Python object iterable.

How do for-in loops work in Python?

At this point we’ve got our Repeater class that apparently supports the iterator protocol, and we just ran a for-in loop to prove it:

repeater = Repeater('Hello')

for item in repeater:

print(item)

A Simpler Iterator Class

Up until now our iterator example consisted of two separate classes, Repeater and RepeaterIterator. They corresponded directly to the two phases used by Python’s iterator protocol:

First setting up and retrieving the iterator object with an iter() call, and then repeatedly fetching values from it via next().

Many times both of these responsibilities can be shouldered by a single class. Doing this allows you to reduce the amount of code necessary to write a class-based iterator.

Generators

Python Generators 101 – The Basics

Let’s start by looking again at the Repeater example that I previously used to introduce the idea of iterators. It implemented a class-based iterator cycling through an infinite sequence of values.

This is what the class looked like in its second (simplified) version:

class Repeater:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

def __iter__(self):

return self

def __next__(self):

return self.value

If you’re thinking, “that’s quite a lot of code for such a simple iterator,” you’re absolutely right. Parts of this class seem rather formulaic, as if they would be written in exactly the same way from one class-based iterator to the next.

This is where Python’s generators enter the scene. If I rewrite this iterator class as a generator, it looks like this:

def repeater(value):

while True:

yield value

Python Generators That Stop Generating

In this tutorial we started out by writing an infinite generator once again. By now you’re probably wondering how to write a generator that stops producing values after a while, instead of going on and on forever.

Thankfully, as programmers we get to work with a nicer interface this time around. Generators stop generating values as soon as control flow returns from the generator function by any means other than a yield statement. This means you no longer have to worry about raising StopIteration at all!

Here’s an example:

def repeat_three_times(value):

yield value

yield value

yield value