reading-notes

https://faroukibrahim-fii.github.io/reading-notes/

Django REST Framework & Docker

A Beginner’s Guide to Docker

Linux Containers

Docker is really just Linux containers which are a type of virtualization.

Virtualization has its roots at the beginning of computer science when large, expensive mainframe computers were the norm. How could multiple programmers use the same single machine? The answer was virtualization and specifically virtual machines which are complete copies of a computer system from the operating system on up.

Containers vs Virtual Environments

If you are a Python programmer (like me) a common question at this point is, what about virtual environments? How do they differ from containers?

Virtual environments are used to isolate Python software packages locally. We can create an isolated box for individual projects so one can use Python 2.7 and Django 1.5 while another can use Python 3.5 and Django 2.1 on the same computer. Virtual environments are great.

But…virtual environments can only isolate Python packages. They still rely on a global, system-level installation of Python albeit they can refer to the proper version. So when we use Python 2.7 in a project, we’re pointing to an installation of Python 2.7 on the computer itself, not actually within the virtual environment.

Hello, World

To confirm Docker installed correctly we can run our first command docker run hello-world. This will download an official image and then run the container. We’ll discuss both images and containers shortly.

$ docker run hello-world

Unable to find image 'hello-world:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/hello-world

1b930d010525: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:9572f7cdcee8591948c2963463447a53466950b3fc15a247fcad1917ca215a2f

Status: Downloaded newer image for hello-world:latest

Hello from Docker!

This message shows that your installation appears to be working correctly.

Images and Containers

Images and containers are the two fundamental concepts to grasp when you start with Docker. An image is a snapshot in time of what a project contains. A container is a running instance of the image.

When we ran hello-world we used an official Docker image. We did not have to create the image ourself. But typically we will create custom images and we do so using a Dockerfile. We also will use docker-compose.yml files to run the containers.

A baking analogy we can use here is as follows:

- A Dockerfile is the recipe for a cake

- An image is a snapshot of the recipe at a given time

- A docker-compose.yml says how to make the cake

- And the container is the actual, baked cake

Images

Ok, let’s create our own image for something more “real.” How about the Python programming language? We can create an image and container just for Python and later add on to it.

First create a local directory on your computer for our code. I’ve chosen to make a code folder on my Desktop (I’m using an Apple computer) and then a python3.7 folder within that.

$ cd ~/Desktop

$ mkdir code && cd code

$ mkdir python3.7 && cd python3.7

Now we need to define the image with a Dockerfile. This is similar to a Pipenv or a requirements.txt file; it is a list of all the requirements needed to build our image. It is simpler to have them all in one place rather than install each manually line-by-line.

If you are on a Mac, you can create a new Dockerfile on the command line using the touch command.

$ touch Dockerfile

Containers

Now that we have our Python image how do we run it? Well just as a Dockerfile is a list of image instructions there is also a docker-compose.yml file that is a list of container instructions.

$ cd ..

$ mkdir djangoapp && cd djangoapp

$ pipenv install django==3.0

$ pipenv shell

Dockerized Django

We’ll now create a Dockerfile for our image which will completely replace our local dev environment, so this will have Python 3 and Django. Then we’ll add a docker-compose.yml for the container instructions. Make each file via the command line.

$ touch Dockerfile

$ touch docker-compose.yml

Library Website and API

Traditional Django

First we need a dedicated directory on our computer to store the code. This can live anywhere but for convenience, if you are on a Mac, we can place it in the Desktop folder. The location really does not matter; it just needs to be easily accessible.

$ cd ~/Desktop

$ mkdir code && cd code

First app

The typical next step is to start adding apps, which represent discrete areas of functionality. A single Django project can support multiple apps.

Stop the local server by typing Control + c and then create a books app.

(library) $ python manage.py startapp books

Models

In your text editor, open up the file books/models.py and update it as follows:

# books/models.py

from django.db import models

class Book(models.Model):

title = models.CharField(max_length=250)

subtitle = models.CharField(max_length=250)

author = models.CharField(max_length=100)

isbn = models.CharField(max_length=13)

def __str__(self):

return self.title

Admin

We can start entering data into our new model via the built-in Django app. But we must do two things first: create a superuser account and update admin.py so the books app is displayed.

Start with the superuser account. On the command line run the following command:

(library) $ python manage.py createsuperuser

Views

The views.py file controls how the database model content is displayed. Since we want to list all books we can use the built-in generic class ListView.

Update the books/views.py file.

# books/views.py

from django.views.generic import ListView

from .models import Book

class BookListView(ListView):

model = Book

template_name = 'book_list.html'

URLs

We need to set up both the project-level urls.py file and then one within the books app. When a user visits our site they will first interact with the config/urls.py file so let’s configure that first. Add the include import on the second line and then a new path for our books app.

# config/urls.py

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path, include # new

urlpatterns = [

path('admin/', admin.site.urls),

path('', include('books.urls')), # new

]

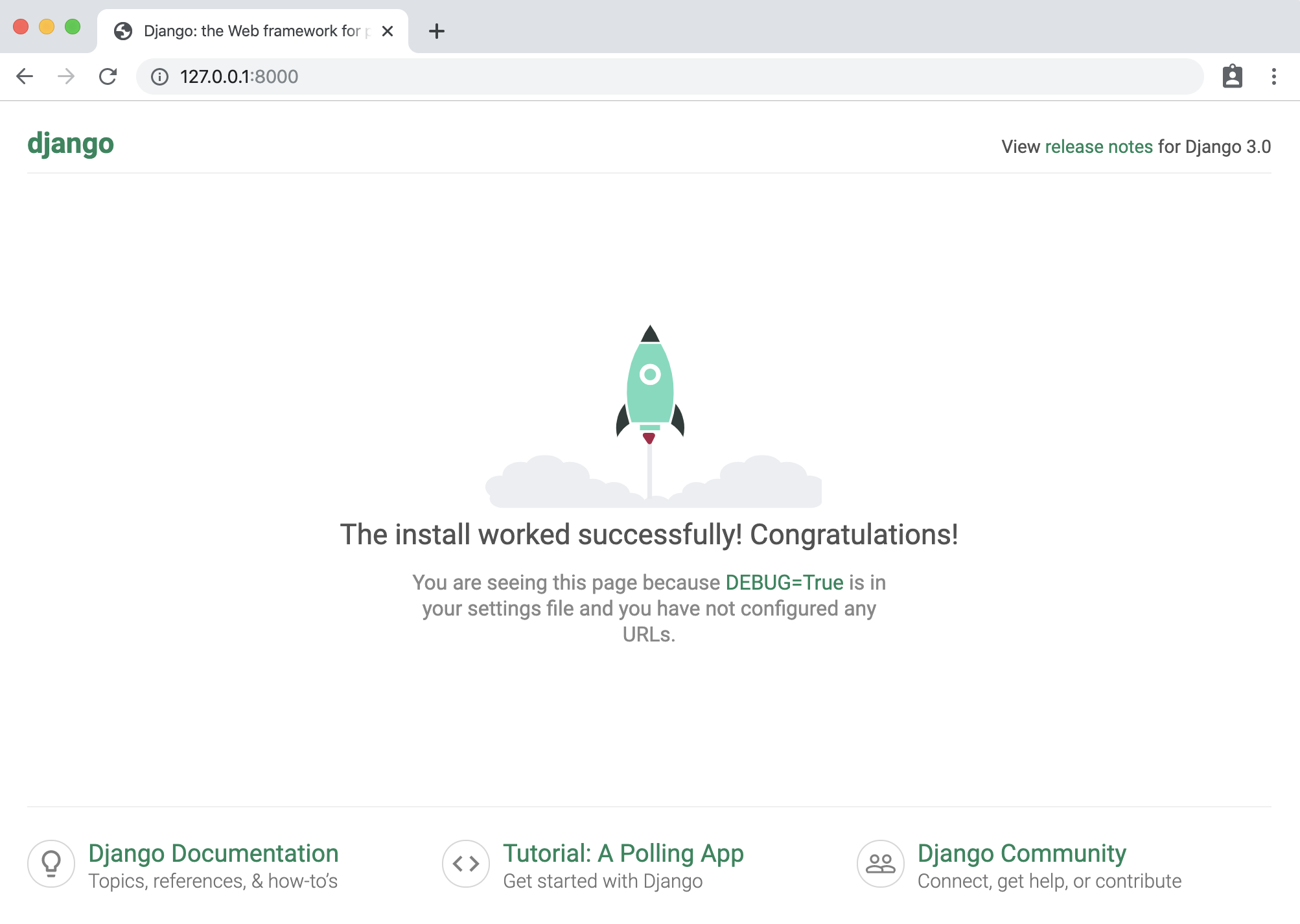

Webpage

Now we can start up the local Django server and see our web page.

(library) $ python manage.py runserver

Django REST Framework

Django REST Framework is added just like any other third-party app. Make sure to quit the local server Control + c if it is still running. Then on the command line type the below.

(library) $ pipenv install djangorestframework~=3.11.0

Views

Next up is our views.py file which relies on Django REST Framework’s built-in generic class views. These deliberately mimic traditional Django’s generic class-based views in format, but they are not the same thing.

Serializers

A serializer translates data into a format that is easy to consume over the internet, typically JSON, and is displayed at an API endpoint. We will also cover serializers and JSON in more depth in following chapters. For now I want to demonstrate how easy it is to create a serializer with Django REST Framework to convert Django models to JSON.

Make a serializers.py file within our api app.

(library) $ touch api/serializers.py

Browsable API

With the local server still running in the first command line console, navigate to our API endpoint in the web browser at http://127.0.0.1:8000/api/.