reading-notes

https://faroukibrahim-fii.github.io/reading-notes/

Automation

Python Regular Expression Tutorial

Regular Expressions, often shortened as regex, are a sequence of characters used to check whether a pattern exists in a given text (string) or not. If you’ve ever used search engines, search and replace tools of word processors and text editors - you’ve already seen regular expressions in use.

Regular Expressions in Python

In Python, regular expressions are supported by the re module. That means that if you want to start using them in your Python scripts, you have to import this module with the help of import:

import re

Basic Patterns: Ordinary Characters

You can easily tackle many basic patterns in Python using ordinary characters. Ordinary characters are the simplest regular expressions.

pattern = r"Cookie"

sequence = "Cookie"

if re.match(pattern, sequence):

print("Match!")

else: print("Not a match!")

Match!

Wild Card Characters: Special Characters

Special characters are characters that do not match themselves as seen but have a special meaning when used in a regular expression.

Grouping in Regular Expressions

The group feature of regular expression allows you to pick up parts of the matching text. Parts of a regular expression pattern bounded by parenthesis () are called groups. The parenthesis does not change what the expression matches, but rather forms groups within the matched sequence. You have been using the group() function all along in this tutorial’s examples.

Greedy vs. Non-Greedy Matching

When a special character matches as much of the search sequence (string) as possible, it is said to be a “Greedy Match”. It is the normal behavior of a regular expression, but sometimes this behavior is not desired:

pattern = "cookie"

sequence = "Cake and cookie"

heading = r'<h1>TITLE</h1>'

re.match(r'<.*>', heading).group()

'<h1>TITLE</h1>'

Function provided by ‘re’

The re library in Python provides several functions to make your tasks easier. You have already seen some of them, such as the re.search(), re.match(). Let’s check out more…

compile(pattern, flags=0)

Regular expressions are handled as strings by Python. However, with compile(), you can computer a regular expression pattern into a regular expression object.

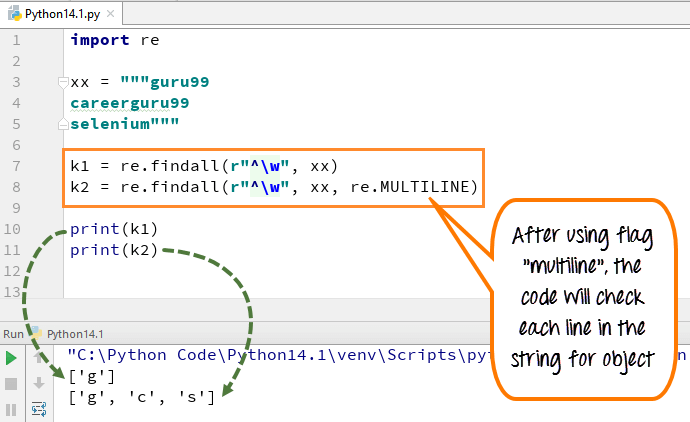

Compilation Flags

Did you notice the term re.IGNORECASE in the last example? Did you figure out its importance?

An expression’s behavior can be modified by specifying a flag value. You can add flags as an extra argument to the different functions that you have seen in this tutorial. Some of the more useful ones are:

- IGNORECASE (I) - Allows case-insensitive matches.

- DOTALL (S) - Allows . to match any character, including newline.

- MULTILINE (M) - Allows start of string (^) and end of string ($) anchor to match newlines as well.

- VERBOSE (X) - Allows you to write whitespace and comments within a regular expression to make it more readable.

shutil — High-level File Operations

Copying Files

copyfile() copies the contents of the source to the destination and raises IOError if it does not have permission to write to the destination file. shutil_copyfile.py

import glob

import shutil

print('BEFORE:', glob.glob('shutil_copyfile.*'))

shutil.copyfile('shutil_copyfile.py', 'shutil_copyfile.py.copy')

print('AFTER:', glob.glob('shutil_copyfile.*'))

Because the function opens the input file for reading, regardless of its type, special files (such as Unix device nodes) cannot be copied as new special files with copyfile().

$ python3 shutil_copyfile.py

BEFORE: ['shutil_copyfile.py']

AFTER: ['shutil_copyfile.py', 'shutil_copyfile.py

Copying File Metadata

By default when a new file is created under Unix, it receives permissions based on the umask of the current user. To copy the permissions from one file to another, use copymode().

# shutil_copymode.py

import os

import shutil

import subprocess

with open('file_to_change.txt', 'wt') as f:

f.write('content')

os.chmod('file_to_change.txt', 0o444)

print('BEFORE:', oct(os.stat('file_to_change.txt').st_mode))

shutil.copymode('shutil_copymode.py', 'file_to_change.txt')

print('AFTER :', oct(os.stat('file_to_change.txt')

Finding Files

The which() function scans a search path looking for a named file. The typical use case is to find an executable program on the shell’s search path defined in the environment variable PATH.

# shutil_which.py

import shutil

print(shutil.which('virtualenv'))

print(shutil.which('tox'))

print(shutil.which('no-such-program'))

If no file matching the search parameters can be found, which() returns None.

$ python3 shutil_which.py

/Users/dhellmann/Library/Python/3.5/bin/virtualenv

/Users/dhellmann/Library/Python/3.5/bin/tox

None

Archives

Python’s standard library includes many modules for managing archive files such as tarfile and zipfile. There are also several higher-level functions for creating and extracting archives in shutil. get_archive_formats() returns a sequence of names and descriptions for formats supported on the current system.

# shutil_get_archive_formats.py

import shutil

for format, description in shutil.get_archive_formats():

print('{:<5}: {}'.format(format, description))

The formats supported depend on which modules and underlying libraries are available, so the output for this example may change based on where it is run.

$ python3 shutil_get_archive_formats.py

bztar: bzip2'ed tar-file

gztar: gzip'ed tar-file

tar : uncompressed tar file

xztar: xz'ed tar-file

zip : ZIP file

File System Space

It can be useful to examine the local file system to see how much space is available before performing a long running operation that may exhaust that space. disk_usage() returns a tuple with the total space, the amount currently being used, and the amount remaining free.

# shutil_disk_usage.py

import shutil

total_b, used_b, free_b = shutil.disk_usage('.')

gib = 2 ** 30 # GiB == gibibyte

gb = 10 ** 9 # GB == gigabyte

print('Total: {:6.2f} GB {:6.2f} GiB'.format(

total_b / gb, total_b / gib))

print('Used : {:6.2f} GB {:6.2f} GiB'.format(

used_b / gb, used_b / gib))

print('Free : {:6.2f} GB {:6.2f} GiB'.format(

free_b / gb, free_b / gib))

The values returned by disk_usage() are the number of bytes, so the example program converts them to more readable units before printing them.

$ python3 shutil_disk_usage.py

Total: 499.42 GB 465.12 GiB

Used : 246.68 GB 229.73 GiB

Free : 252.48 GB 235.14 GiB