reading-notes

https://faroukibrahim-fii.github.io/reading-notes/

Game of Greed 2

Understanding Scope

In programming, the scope of a name defines the area of a program in which you can unambiguously access that name, such as variables, functions, objects, and so on. A name will only be visible to and accessible by the code in its scope. Several programming languages take advantage of scope for avoiding name collisions and unpredictable behaviors. Most commonly, you’ll distinguish two general scopes:

-

Global scope: The names that you define in this scope are available to all your code.

-

Local scope: The names that you define in this scope are only available or visible to the code within the scope.

Scope came about because early programming languages (like BASIC) only had global names. With this kind of name, any part of the program could modify any variable at any time, so maintaining and debugging large programs could become a real nightmare. To work with global names, you’d need to keep all the code in mind at the same time to know what the value of a given name is at any time. This was an important side-effect of not having scopes.

Names and Scopes in Python

Since Python is a dynamically-typed language, variables in Python come into existence when you first assign them a value. On the other hand, functions and classes are available after you define them using def or class, respectively. Finally, modules exist after you import them.

Python Scope vs Namespace

In Python, the concept of scope is closely related to the concept of the namespace. As you’ve learned so far, a Python scope determines where in your program a name is visible. Python scopes are implemented as dictionaries that map names to objects. These dictionaries are commonly called namespaces. These are the concrete mechanisms that Python uses to store names. They’re stored in a special attribute called .dict.

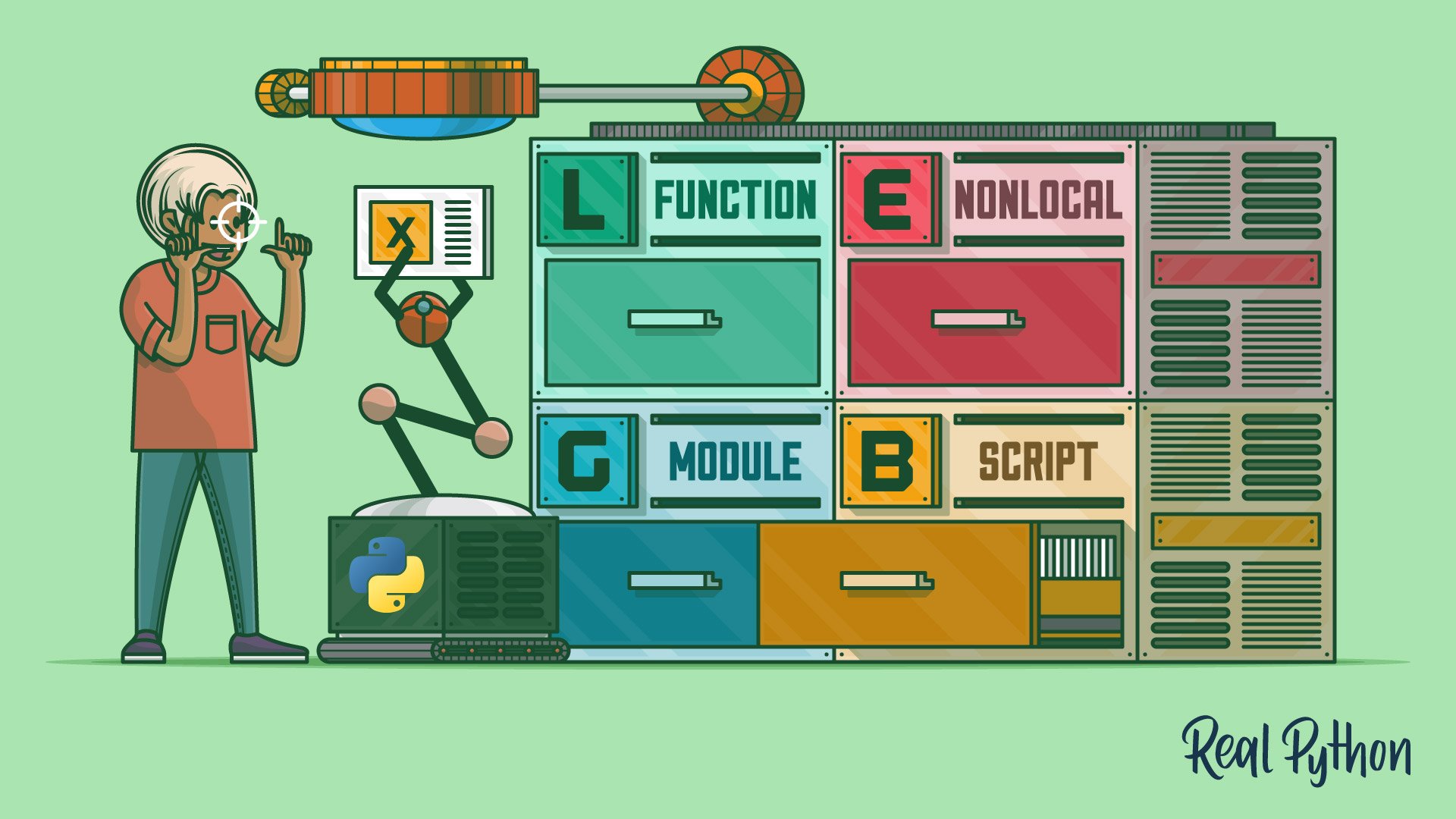

Using the LEGB Rule for Python Scope

Python resolves names using the so-called LEGB rule, which is named after the Python scope for names. The letters in LEGB stand for Local, Enclosing, Global, and Built-in. Here’s a quick overview of what these terms mean:

-

Local (or function) scope is the code block or body of any Python function or lambda expression. This Python scope contains the names that you define inside the function. These names will only be visible from the code of the function. It’s created at function call, not at function definition, so you’ll have as many different local scopes as function calls. This is true even if you call the same function multiple times, or recursively. Each call will result in a new local scope being created.

-

Enclosing (or nonlocal) scope is a special scope that only exists for nested functions. If the local scope is an inner or nested function, then the enclosing scope is the scope of the outer or enclosing function. This scope contains the names that you define in the enclosing function. The names in the enclosing scope are visible from the code of the inner and enclosing functions.

-

Global (or module) scope is the top-most scope in a Python program, script, or module. This Python scope contains all of the names that you define at the top level of a program or a module. Names in this Python scope are visible from everywhere in your code.

-

Built-in scope is a special Python scope that’s created or loaded whenever you run a script or open an interactive session. This scope contains names such as keywords, functions, exceptions, and other attributes that are built into Python. Names in this Python scope are also available from everywhere in your code. It’s automatically loaded by Python when you run a program or script.

Functions: The Local Scope

The local scope or function scope is a Python scope created at function calls. Every time you call a function, you’re also creating a new local scope. On the other hand, you can think of each def statement and lambda expression as a blueprint for new local scopes. These local scopes will come into existence whenever you call the function at hand.

Nested Functions: The Enclosing Scope

Enclosing or nonlocal scope is observed when you nest functions inside other functions. The enclosing scope was added in Python 2.2. It takes the form of the local scope of any enclosing function’s local scopes. Names that you define in the enclosing Python scope are commonly known as nonlocal names.

Modules: The Global Scope

From the moment you start a Python program, you’re in the global Python scope. Internally, Python turns your program’s main script into a module called main to hold the main program’s execution. The namespace of this module is the main global scope of your program.

builtins: The Built-In Scope

The built-in scope is a special Python scope that’s implemented as a standard library module named builtins in Python 3.x. All of Python’s built-in objects live in this module. They’re automatically loaded to the built-in scope when you run the Python interpreter. Python searches builtins last in its LEGB lookup, so you get all the names it defines for free. This means that you can use them without importing any module.

Modifying the Behavior of a Python Scope

So far, you’ve learned how a Python scope works and how they restrict the visibility of variables, functions, classes, and other Python objects to certain portions of your code. You now know that you can access or reference global names from any place in your code, but they can be modified or updated from within the global Python scope.

You also know that you can access local names only from inside the local Python scope they were created in or from inside a nested function, but you can’t access them from the global Python scope or from other local scopes. Additionally, you’ve learned that nonlocal names can be accessed from inside nested functions, but they can’t be modified or updated from there.

The global Statement

You already know that when you try to assign a value to a global name inside a function, you create a new local name in the function scope. To modify this behavior, you can use a global statement. With this statement, you can define a list of names that are going to be treated as global names.

The nonlocal Statement

Similarly to global names, nonlocal names can be accessed from inner functions, but not assigned or updated. If you want to modify them, then you need to use a nonlocal statement. With a nonlocal statement, you can define a list of names that are going to be treated as nonlocal.

Using Enclosing Scopes as Closures

Closures are a special use case of the enclosing Python scope. When you handle a nested function as data, the statements that make up that function are packaged together with the environment in which they execute. The resulting object is known as a closure. In other words, a closure is an inner or nested function that carries information about its enclosing scope, even though this scope has completed its execution.

Bringing Names to Scope With import

When you write a Python program, you typically organize the code into several modules. For your program to work, you’ll need to bring the names in those separate modules to your main module. To do that, you need to import the modules or the names explicitly. This is the only way you can use those names in your main global Python scope.

Discovering Unusual Python Scopes

You’ll find some Python structures where name resolution seems not to fit into the LEGB rule for Python scopes. These structures include:

- Comprehensions

- Exception blocks

- Classes and instances

Comprehension Variables Scope

The first structure you’ll cover is the comprehension. A comprehension is a compact way to process all or part of the elements in a collection or sequence. You can use comprehensions to create lists, dictionaries, and sets.

Comprehensions consist of a pair of brackets ([]) or curly braces ({}) containing an expression, followed by one or more for clauses and then zero or one if clause per for clause.

Exception Variables Scope

Another atypical case of Python scope that you’ll encounter is the case of the exception variable. The exception variable is a variable that holds a reference to the exception raised by a try statement. In Python 3.x, such variables are local to the except block and are forgotten when the block ends.

Class and Instance Attributes Scope

When you define a class, you’re creating a new local Python scope. The names assigned at the top level of the class live in this local scope. The names that you assigned inside a class statement don’t clash with names elsewhere. You can say that these names follow the LEGB rule, where the class block represents the L level.

In general, when you’re writing object-oriented code in Python and you try to access an attribute, your program takes the following steps:

- Check the instance local scope or namespace first.

- If the attribute is not found there, then check the class local scope or namespace.

- If the name doesn’t exist in the class namespace either, then you’ll get an AttributeError.

Using Scope Related Built-In Functions

There are many built-in functions that are closely related to the concept of Python scope and namespaces. In previous sections, you’ve used dir() to get information on the names that exist in a given scope. Besides dir(), there are some other built-in functions that can help you out when you’re trying to get information about a Python scope or namespace. In this section, you’ll cover how to work with:

- globals()

- locals()

- dir()

- vars()

globals()

In Python, globals() is a built-in function that returns a reference to the current global scope or namespace dictionary. This dictionary always stores the names of the current module. This means that if you call globals() in a given module, then you’ll get a dictionary containing all the names that you’ve defined in that module, right before the call to globals().

locals()

Another function related to Python scope and namespaces is locals(). This function updates and returns a dictionary that holds a copy of the current state of the local Python scope or namespace. When you call locals() in a function block, you get all the names assigned in the local or function scope up to the point where you call locals().

vars()

vars() is a Python built-in function that returns the .dict attribute of a module, class, instance, or any other object which has a dictionary attribute. Remember that .dict is a special dictionary that Python uses to implement namespaces.

dir()

You can use dir() without arguments to get the list of names in the current Python scope. If you call dir() with an argument, then the function attempts to return a list of valid attributes.